The Noble Art of Self Defense in China the Chuba Review

Introduction

This is the second half of our two part serial on the life and writings of Alfred Lister. A civil servant in Hong Kong during the second one-half of the 19th century, Lister provided his readers with some of the most detailed English language discussions of the Chinese martial arts to emerge during the 1870s. In the first part of this post (see here) we reviewed the biographical details of Lister's life, and looked at the initial emergence of his involvement in the Chinese martial arts. It tin be argued that this was a natural outgrowth of his efforts to translate the various sorts of "street literature" that he found in Hong Kong's many market stalls. These initial efforts tended to be more than "literary" in character and were published under Lister'due south own proper name.

In today'southward post we will plough our attention to Lister's two major descriptive treatments of the Chinese martial arts. The get-go of these was a newspaper article, while the other was an essay in the Prc Review (one of his favorite publications). Unfortunately both pieces were published anonymously, due both to their content (battle of any blazon was not entirely respectable in the 1860s and 1870s), and because the second of these accounts included a number of sharp attacks on Lister'due south colleagues in Hong Kong. As such, our first challenge will exist to look at the external and internal evidence necessary to address the question of authorship. Afterward that we volition enquire how these two new sources relate to the Lister's emerging discourse on Chinese boxing.

Our efforts will be handsomely rewarded as it turns out that Lister was ane of the most of import 19th century observers of the Chinese martial arts. Both of these sources have been previously discussed on Kung Fu Tea, but in neither instance did I endeavor to identify an author. The outset of these actually predates Lister'south 1873 translation of "A-lan's Squealer" (discussed in part I) and may take been part of his groundwork inquiry on the nature of Chinese boxing while producing the translation of this Kung Fu laden opera. On July of 1872 the North Mainland china Herald (a widely read English language language paper) ran an anonymous article editorializing on a recent issue titled simply "Chinese Boxing."

If you lot have non nevertheless done and so please consider reading the showtime one-half of this essay. The discussion below follows directly upon what was already posted.

"Chinese Boxing" in the North China Herald.

At that place can be no doubt that this article was 1 of the most interesting 19th century statements by Western observers of the Chinese martial arts. Those who have read Lister's previous commentaries volition notice a familiar ring in this author's biting tones. Anyone wishing to review the substance of his account (an examination of the social consequences of a death in a challenge match fought over a gambling debt) can practise so here. Indeed, one suspects that it was the connection between market place gambling and boxing that propelled Lister'southward pen equally he worked on his translation of "A-lan's Grunter" (a story in which 2 such gentlemen play an important role).

For our current purposes it is necessary to review the story'south introduction, including a passage omitted from my previous discussions of the piece, in which the writer tackles questions of translation and the social equivalence of Chinese and Western Boxing.

"If there is one particular rather than another in which we might least expect to discover John Chinaman resemble John Bull, it is in the exercise of boxing. The meek celestial does get roused occasionally, but he usually declines a paw to manus come across, unless impelled by the courage of despair. He is generally credited with a keen appreciation of the advantages of running away, equally compared with the treat of continuing upward to exist knocked down, and is slow to claim the loftier privilege the ancients thought worthy to be immune only to freemen, of being beaten to the consistency of a jelly.

How the race must rise in the estimation of foreigners, therefore, when we mention that the noble fine art of cocky-defence and legitimate aggressiveness flourished in Mainland china centuries probably earlier the "Fancy" always formed a ring in that United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland which has come up to exist regarded as the home of boxing. Of grade, similar everything else in China, the science has rather deteriorated than improved; its exercise is crude; its laws unsystematized; its Professors are not patronized by royalty or nor petted by a sporting public; the institution is a vagabond ane, just an establishment none the less.

Professors of the art, chosen "fist-teachers," offer their services to initiate their countrymen in the use of their "maulies," and, in addition in throwing out their feet in a dexterous way…

…Boxing clubs are kept up in country villages, where pugilists meet and contest the honours of the band. Unfortunately, popular literature does not take cognizance of the little "mills" in which the Chinese boxer "may come up smiling after round the twenty-fifth," nor are the referees, if there be whatsoever, correspondents of sporting papers, so that we are unable to tell whether the language is rich in such synonyms as "nob," and "conk," and "peepers," and "potato-trap." Merely if boxers appreciate, every bit much as their strange brethren, the advantages over an ignorant and admiring mob which the supposition of a peculiar knowledge gives, we may well suppose that, as they smoke their pipe and sip there tea, they hash out the prowess of the Soochow Slasher or the Chefoo Chicken in a terse and mystic phraseology, embellished with rude adjectives and eked out by expressive winks." (emphasis added).

Even though there is no prove that the 2 gamblers involved in the fatal fighter viewed their run across every bit a sporting event, Lister over again adopts "the Fancy" as his lens for both making sense of these events and explaining them to his reader. Points of similarity and difference are carefully noted. Yet the author refers to these practices as "the noble art of self-defense", a phrase without any real equivalent in the earth of the nineteenth century Chinese martial arts, still one that had get synonymous with English pugilism during this era. Readers were left with no question as to the advisable prototype for interpreting these events.

The repeated, and always ironic, invocation of this specific phrase seems to be something of a hallmark of Lister'south writing on the topic. Indeed, information technology is repeated (and even emphasized) in each of the 4 of the discussions of the Chinese martial arts that tin can be traced directly to him. While other authors of the period made references to "Chinese battle" in general, this longer conception appears much more rarely.

Needless to say, past whatever name, the Chinese martial arts fared desperately in Lister's business relationship. The two gamblers manage to destroy (and in one example end) their lives through their ill-fated challenge match. They appear nearly equally hapless as the characters in "A-lan's Pig."

What is interesting to note, however, is that their Western brethren practise not come off much better. Indeed, the writer's point is precisely that the deviation in these pursuits is one of degree rather than kind. In both cases he perceives similarly situated institutions in which a grouping of marginal individuals create a torso of esoteric knowledge (and merely as importantly, a specific language) that grants them the illusion of social continuing. Yet ultimately the idea of continuing up to be "beaten to the consistency of a jelly" is just equally foolish in a Western battle ring every bit a Chinese marketplace. Indeed, Lister's extended exploration of Western boxing terminology ensures that his critique is aimed just as squarely at the onetime as the latter.

Reader's should besides note that the writer of this account has evidently been searching the popular literature of southern China in hopes of coming across a sustained discussion of the hand combat customs. While he initially indicates that he found cipher, Lister'southward luck seems to take changed former betwixt the cease of 1872 and 1874.

In 1874 Lister published what is probably the unmarried near of import period account of the Southern Chinese martial arts to appear during the 19th century. His nigh comprehensive statement on the field of study ran in The China Review (Vol. 3 No. 2), and was titled "The Noble Art of Cocky-Defence force in Red china." Once again, it was Lister's dandy involvement in popular literature that brought this work to light.

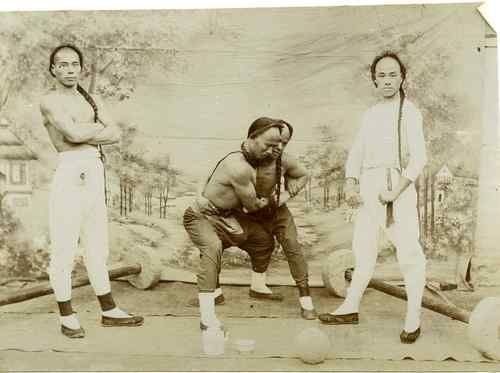

Like his earlier 1873 article in the aforementioned publication ("A Chinese Farce"), this work also purported to be a "directly translation" of a pamphlet or penny book that he had been caused from a local book stall. He notes that the publication in question was very inexpensive and contained a number of crudely executed woodcuts. It promised its readers two lessons in unarmed boxing, iii discussions of staff fighting, and seven more focusing on swords, shields and diverse polearms.

Perhaps the most important thing to note about this small piece of work is the mere fact of its being. In Kennedy and Gao'southward very informative reference work, they note the beingness of a number of distinct genres of martial arts manuals during the tardily imperial and Democracy period. Lister's fight book does not fit within any known category. Specifically, they state that while hand copied manuscripts were circulated during the Qing era, printed manuals meant for commercial sale were not developed until the Republic era renaissance of interest in the traditional martial arts.

Yet Lister is conspicuously describing a printed martial arts manual (produced using woods blocks) decades earlier the end of the dynasty. In fact, a close examination of the historical sources reveal at least one other Western observer encountered a similar volume (with an additional emphasis on strength grooming), equally early as 1830. Remarkably, non one of these pamphlets is known to accept survived, which makes Lister'south detailed clarification of the volume and its contents all the more of import.

Modern historians will exist disappointed to notation that, while Lister reproduced a number of the original forest blocks prints, his "translation" of this text was fifty-fifty more of a transformation than what he offered readers of "A Chinese Farce." Afterward an extensive (and revealing) word of the social milieu from which this book arises, he informs his readers that:

"The title of the little pamphlet placed at the head of this paper is non in the least a free translation, merely literal. It is a fact that, for less than a penny, you buy at a stall in a Chinese street a brochure called, in and so many words, The noble art of self-defence force, and that the purchaser who is about to read it volition be curiously reminded of any he may have heard of the slang of the ring at home, by phrases, not so literally exact as the above simply quite sufficiently suggestive of "stand business firm on your pins," "popular in your left," "hit straight from the shoulder," and "permit him take it in the staff of life-basket."

Again, the substance of this work has previously been discussed elsewhere. All the same even the curt paragraph in a higher place suggests much that must exist considered. We once again meet the author's interest in drawing an equivalence between the esoteric language of Western and Eastern boxing. Whereas the existence of a shared mechanism of gaining legitimacy through linguistic communication was suggested in the North Communist china Herald article of 1872, at present Lister claims to have found confirmation of his hypothesis in the popular martial arts literature itself.

Readers volition also note that Lister has returned to once again meditate on "the noble fine art of self-defense force." It is claimed (rather improbably) that this English language language idiom is a literal translation of the book'due south Chinese title. Of course in the very next line this assuming proclamation is qualified with the more pocket-sized, "in and so many words." This fractional walking back really suggests something other than "an exact translation" might be at play.

In this case Lister has done his readers the favor of including the characters of the text'south actual Chinese title (雄拳拆法)in the very first footnote of his article. Every bit one would probably wait, the actual championship has piddling do with "cocky-defense," noble or otherwise.

After examining the question Douglas Wile has concluded that possibly a more accurate translation of the included characters might be "Fierce Down Techniques of Hero Boxing." He notes that first ii characters 雄拳 would be something like "Hero Boxing" or "Martial Art of the Hero." "Hero Boxing" is a term that still exists within the region's martial arts today.

拆法, the second set of characters, is a scrap more mysterious. Wile further wonders "if it could be a term for 'martial arts' in a local dialect, since the book seems to take been written for the "street." 法 by itself tin exist equally broad as style and as narrow as technique" (Personal correspondence).

The suggestion of a local connexion is an interesting one. A number of existing Choi Li Fut schools use the 雄拳construction (often with an additional modifier). Farther, at one point in his background give-and-take to the translation Lister offers the following description of a sparring exercise in which two local boxers were induced to habiliment western way battle gloves:

"Anything more exquisitely ludicrous than a couple of Chinese induced to put on the gloves (afterwards an example of their employ from Englishman) I have never seen. They cautiously backed on each other until the seats of their trousers near touched, each one bending himself nearly double to avoid the imagined terrific blows his adversary was aiming at his head, and at the same time striking vaguely round in what schoolboys call the Windmill fashion."

Subsequently stripping the invectives from this business relationship, ane is left with the idea of deep stances and wide, swinging, directly armed blows. Such a description is certainly reminiscent of Choy Li Fut, which was perhaps the most popular martial art throughout the Pearl River delta region at the time that Lister carried out his investigation.

Then once again, the name of the first unarmed technique in the book, "The Hungry Tiger Seizes the Sheep" is besides seen in modern Hung Gar. While I am non sure that Lister'south reconstruction of the technique is descriptively accurate, the illustration of figure B in the first forest cutting does bear a sure resemblance to how the technique is still described today.

While it may not be possible to trace this small pamphlet to a specific school, the techniques which it lists are clearly present in the southern Chinese martial arts. Readers may besides note, for example, the appearance of the area's distinctive hudiedao in fig. VI, consummate with handguards.

Given the importance of this text to our agreement of the Southern Chinese martial arts, resolving the question of authorship is particularly important. Unlike the 1872 article on Chinese Battle, this text is not totally anonymous. Information technology lists an author past the initials (or acronym) Fifty.C.P. In itself this is not unusual as many of the early entries in The Communist china Review had authors who were equally cryptic.

When attempting to unravel this mystery modern students have two sources of prove that they can draw on. There are those clues that are found within the text, and those that come up from outside of it. In this instance the external evidence is clearer so nosotros volition start there.

"The Noble Art of Self-Defense in Prc" was exciting enough that the commodity was not shortly forgotten by its readers. It was actually reprinted in at least ii other cases that I have been able to identify. Most notably, in 1884 The China Mailreprinted large sections of this article with its ain (horrifyingly racist) introduction provided by the paper's editor. This same editor, when commenting on the piece, mentioned that it was originally written past Alfred Lister, and went on to list the positions that Lister was currently holding in Hong Kong's government. Given that Lister's earlier comments on Chinese boxing were published under his own name (1870 and 1873), and his already noted penchant for translating a broad range of pop literature, this identification seems plausible.

In terms of textual testify, there are a number of quirks that nosotros could point to. These including the writer's ongoing fascination with applying the idiomatic expression "the noble arts of self-defence" to Chinese manus combat, his sardonic habit of bequeathing upon his readers "literal translations" that were clearly anything but ("I my stand on fol-lol, I stake my reputation on fol-lol!"), and the repeated efforts to draw connections between Chinese and Western boxing not merely on a social just too a linguistic level.

If that were not enough, "L.C.P." seems to wink at his existent identity in a number of places. Any reader who actually went through the footnotes would quickly notice that Lister really cites and draws on his own give-and-take of "A Chinese Farce" in the course of his translation of "The Noble Art of Self-Defence in China."

So why the elaborate charade? In the 1870s it was acceptable for a civil servant, and trained translator, to employ his skills equally a literary critic in the public discussion of scholarly works. Yet it was probably less appropriate to put i'due south ain name on such frivolous activities as publishing amateur poetry or investigating the various ways in which professional person gamblers and actors spent their free time.

A close reading of this text suggests that at that place may have been other reasons besides. To begin with, the expatriate community in Hong Kong was not that big during the 1870s, and Lister launched some stinging attacks against his colleagues and beau residents in the opening pages of this article. Ane of the more serious of these attacks was a straight rebuke to a fellow jurist in serving in the court arrangement. Lister also lampooned the frustrations and failures of a (probably well known) visiting VIP to replicate the feats of strength usually adept by Chinese soldiers.

1 suspects that quite a few people would take been able to guess immediately at the real identity of the author of this article (particularly when specific statements made in court were beingness quoted). Indeed, such politically ill-brash behavior may explain why the individual who wrote Lister'south anonymous obituary in 1890 observed that he was often lonely and died with few friends. Publishing under a creatively obscure acronym probably provided Lister enough of a fig leafage to get about his daily work. And his connection to this work was just scandalous enough to allow the editor ofThe Red china Mail to take pleasure in outing him when he served as the colony's treasurer.

Assessing the Contribution

The evidence presented hither suggests that betwixt 1869 and 1874 Alfred Lister, in addition to his many duties inside the Hong Kong Civil Service, undertook a proto-sociological study of the Chinese martial arts. He produced at least four published statements (1870, 1872, 1873 and 1874) on the topic. In two cases (1870 and 1873) he signed these with his ain name. And in two more (1872 and 1874) both external and internal show strongly suggest his authorship.

Lister was non overly sympathetic towards the Chinese martial arts, nonetheless he made some important sociological observations. He noted that the public operation of the martial arts was a form of marketplace entertainment associated with the selling of patent medicine. These aforementioned arts were commonly found within gambling houses. The arts that civilians did (while clearly not identical) were related in fundamental ways to the practices that soldiers cultivated in their garrison houses. And finally, all of this was connected to the opera (a major institution within traditional Chinese social club), in ways that modernistic historians are yet struggling to understand. Every bit he noted in 1874:

"It is probably actors out of employ who brand a precarious living past exhibiting, and professing to teach these tricks in the street. Contemptable every bit they may seem to a man fresh from Oxford, information technology cannot exist denied that they often exhibit surprising quickness, strength and agility." (86)

Nor can we ignore the importance of Lister'southward writings as a historical artifact. In publishing a partial translation and transcription of "The Noble Art of Self-Defence in Red china" he preserved a surprisingly detailed record of a genre of popular writing on the Chinese martial arts that has survived nowhere else. Indeed, this pocket-size text compliments and sits on the same level as the Bubishi (a hand written manuscript tradition that survived only in Okinawa) every bit witnesses to the nature of late xixth century southern Kung Fu.

Perchance the greatest force of Lister's writing was his conclusion to brand all of this accessible to the English language linguistic communication reading public, fifty-fifty if that meant arguing for unconventional methods of translation. The fact that his works were reprinted by multiple outlets during the coming decades suggests the degree to which his descriptions gripped the public's imagination. What had not been washed, prior to this serial, was to publicly identify the full range of texts that Lister authored and to demonstrate how his understanding grew over time.

Lister's give-and-take of Chinese boxing was non without serious flaws. His finely tuned sense of "the ridiculous" oft outstripped his ethnographic curiosity. And while he correctly identified a number of the sectors of Chinese order that supported the martial arts (military machine, theater, medicine, gambling…) his inability to set up aside his western categories of understanding meant that he was never able to identify cadre values or appreciate the identities that lay across these practices.

When comparing the Chinese martial arts to their supposed western counterparts Lister saw mainly their shortcomings. For him traditional paw combat would e'er remain an unscientific version of Western boxing or a backwards method of military training. Defective a general theory of the nature and purpose of the martial arts, he was ultimately unable to make sense of what he saw, fifty-fifty while he was forced to acknowledge the surprising forcefulness and speed of specific boxers.

In the last analysis one is left to wonder what Lister would accept learned nigh the Chinese martial arts if he had joined those soldiers from Canton equally they practiced in front of their billet, rather than but observing them from a distance. Would practicing the Chinese martial arts have forced him to confront these deeper questions of pregnant, civilisation and identity? Or lacking a theoretical foundation, would these experiences but accept get another bullheaded spot?

oOo

If yous enjoyed this essay yous might also desire to read: Butterfly Swords and Boxing: Exploring a Lost Southern Chinese Martial Arts Training Manual.

oOo

Source: https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2019/04/14/revisiting-alfred-lister-the-noble-art-of-self-defense-in-china-part-ii/

0 Response to "The Noble Art of Self Defense in China the Chuba Review"

Post a Comment